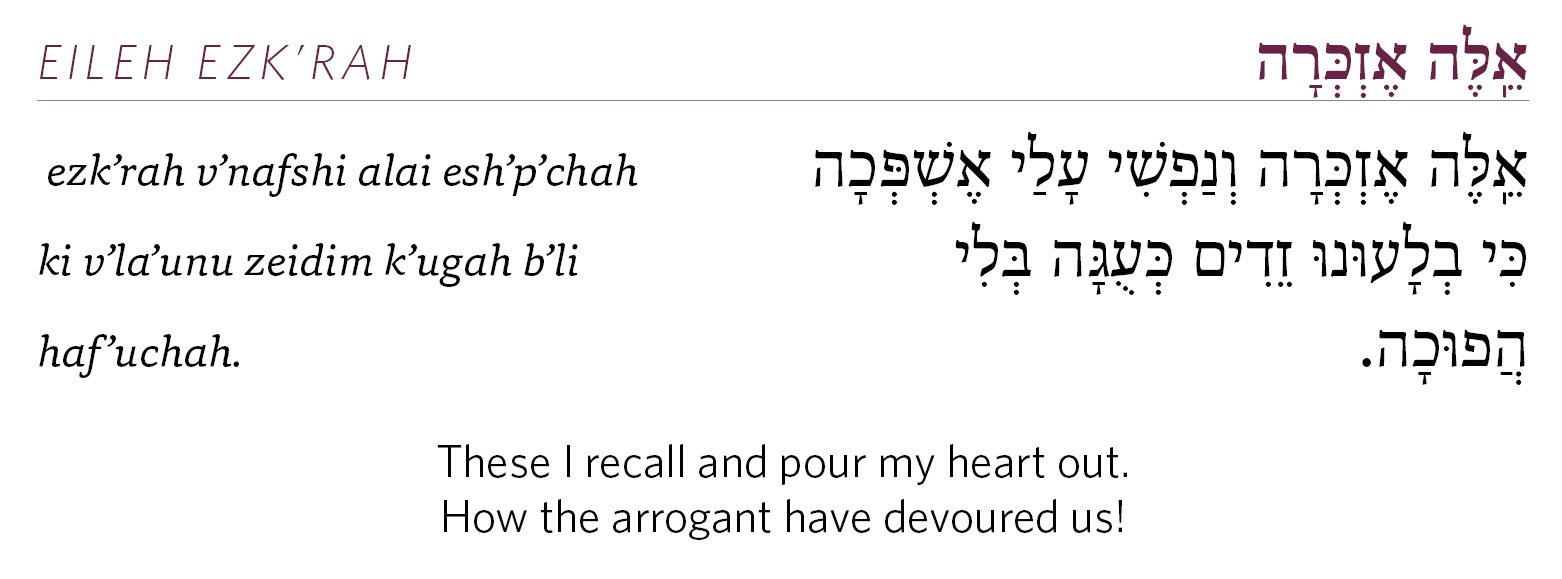

The words above (as they appear in the Wise High Holy Day prayer book) come from the Yizkor service for Yom Kippur. As we gather to mourn our own dead, our emotions raw and exposed by the “awesome power of this day,” our tradition bids us to turn our thoughts toward the martyrs of our people. We recount the sufferings of ages past and recognize that to be a Jew is to be forever bound to history. Nothing is ever truly past and forgotten; everything that our ancestors endured and cherished continues to live in us. Our holy days revolve around ancient events even as modern circumstances are layered over them. For example, the Passover seder is not limited to recounting the Egyptian exodus, we’ve added sections about the Shoah and other historical events.

In so many ways, that is a blessing and a curse. The blessing is that we hold our past close, able to stand ready to learn from what has transpired as we endeavor to face the present and future. The curse is that we’ll view contemporary events through the lens of the past and fail to recognize that though there certainly may be analogies, modern circumstances might demand entirely different responses.

In his post-October 7th essay, titled The Memory Trap, Hartman scholar James Loeffler wrote the following:

Tragically, this past year has forced us to confront the meaning and value of martyrdom as members of the Jewish community. Now, because of October 7th, we must confront martyrdom in our modern world. There is no doubt that those struck down in the early hours of October 7th, some in rapturous dancing, others just opening their eyes on the sunrise of a new day, are martyrs.

In Jewish tradition, and reflected in the placement of martyrology themes in Yom Kippur, the deaths of martyrs atone for the sins of the people. It is the way that our ancestors sought to make sense of the sense-less. How else to explain the death of innocents?

We are left with no less of a dilemma. What sense will we make of the martyrs of our generation? Does their martyrdom atone? For them, for us? How do we bear witness to their atonement? In a side bar of our Machzor, my colleague, Rabbi Sari Laufer wrote: Jewish tradition understands a martyr as one who dies al Kiddush Hashem (for the sanctification of God’s name), who are murdered for being Jews, celebrating Jewish life, and teaching Torah and its values.

How will we sanctify their memories by our deeds and our re-telling of their stories? Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote:

The book of life remains open for us to continue writing our story. The weight of our martyrs hangs heavily in our thoughts. The choices we make, the paths we follow, the world we struggle to build, is our act of solidarity with them and our pursuit Kiddush haShem. May we be blessed in our efforts.

— Rabbi Ron Stern